Abusing the Process Working Set

Understanding the Working Set in Windows

The working set of a Windows process refers to the collection of pages in its virtual address space that the process has recently referenced. This set includes shared data, such as libraries used by multiple processes and private data unique to the process. The virtual memory manager optimizes performance by keeping only the necessary pages in memory, minimizing the overall demand on physical memory.

The virtual memory system in Windows is designed to balance efficiency and resource usage. By maintaining a working set, the system can avoid loading all possible pages into memory. This selective loading process ensures that memory is available for other processes and tasks, making the system more responsive.

However, not all memory pages are kept in the working set at all times. Pages that haven’t been used recently may be paged out to disk to free up memory for more active processes. When the application needs to access this paged-out memory unexpectedly, a page fault occurs.

What is a Page Fault?

A page fault happens when a process attempts to access a page not currently loaded into its working set. When this occurs, the operating system pauses the process, retrieves the required page from the disk, and loads it back into memory. Although this mechanism allows the system to manage memory efficiently, frequent page faults can degrade performance since accessing data from disk is slower than accessing it from memory.

Detecting Page Faults

Now that we understand what a page fault is, the next question is: how can we detect when one occurs? Fortunately, Windows provides tools to help us monitor memory activity. One such tool is the GetWsChanges function in the Windows API. This function allows us to retrieve information about the pages that have been added to or removed from the working set of a specified process since its initialization.

Below is a C++ implementation of a working set watcher. It uses GetWsChangesEx to gather the list of pages that have been added to or removed from the working set of the monitored process. It then checks if any of the faulting addresses are part of a predefined watch list and logs the details, including the thread ID and process information.

void watcher::watch( std::stop_token token ) const

{

std::vector< PSAPI_WS_WATCH_INFORMATION_EX > buffer( 100 );

while ( !token.stop_requested( ) )

{

const auto size = buffer.size( );

auto cb = static_cast< DWORD >( size * sizeof( PSAPI_WS_WATCH_INFORMATION_EX ) );

// Clear the buffer and resize it to the required size.

buffer.clear( );

buffer.resize( size );

if ( !GetWsChangesEx( handle, buffer.data( ), &cb ) )

{

const auto error = GetLastError( );

// This isn't an error, just no changes in the working set since the last call.

if ( error == ERROR_NO_MORE_ITEMS )

{

// Wait a bit until we try again

std::this_thread::sleep_for( 1s );

continue;

}

// Any other error code is a real error.

if ( error != ERROR_INSUFFICIENT_BUFFER )

throw std::runtime_error( std::format( "Failed to get working set changes: {0}", error ) );

// Resize the buffer to the required size.

buffer.resize( cb / sizeof( PSAPI_WS_WATCH_INFORMATION_EX ) );

continue;

}

// At this point, we have an array of pages that have been added or removed from the working set. Now

// lets see if we have a page that we care about.

for ( const auto& entry : buffer )

{

if ( entry.BasicInfo.FaultingPc == nullptr )

continue;

const auto faulting_va = reinterpret_cast< std::uintptr_t >( entry.BasicInfo.FaultingVa );

const auto faulting_page_va = page_align( faulting_va );

// Check if the current page is in the watch list.

if ( std::find( watch_list.begin( ), watch_list.end( ), faulting_page_va ) != watch_list.end( ) )

{

// Get the the process id of the thread that caused the fault.

const auto pid = get_process_id( entry.FaultingThreadId );

// If this is our process, then we can ignore it.

if ( pid == GetCurrentProcessId( ) )

continue;

// Print the faulting PC and the faulting VA.

std::println(

"[+] 0x{:x} (0x{:x}) was mapped by (TID: {}) @ {}",

faulting_page_va,

faulting_va,

entry.FaultingThreadId,

entry.BasicInfo.FaultingPc );

// Get the process path.

const auto path = get_process_path( pid );

// Print the process path.

std::printf( "\t--> %ws (PID: %lu)\n", path.c_str( ), pid );

}

}

// Wait a bit until we try again

std::this_thread::sleep_for( 1s );

}

}This code is part of the loop body for a

std::jthreadwhich is why it has a stop token.

Creating and Managing Allocation

In the example above, the watch_list contains a list of virtual addresses corresponding to memory pages that should not be paged back into the working set. These allocations are crucial for ensuring that specific memory regions remain outside the working set, reducing their impact on system performance and memory pressure.

To achieve this, all allocations referenced in the watch_list must be created using the VirtualAlloc function, a Windows API method that allows you to allocate memory in a process’s virtual address space. VirtualAlloc provides control over the allocation size, memory protection, and type, allowing the creation of memory regions that can later be managed for paging.

Once these allocations are made, the pages need to be paged out of the working set. This can be done by calling the VirtualUnlock function on the allocated memory region. VirtualUnlock removes the specified pages from the process's working set, forcing them to reside in the page file on disk rather than in physical memory. This prevents the pages from being accessed directly until they are paged back in as needed by the system.

template< typename T, typename... Args >

paged_ptr< T > make_paged( Args&&... args )

{

const auto buffer = VirtualAlloc( nullptr, sizeof( T ), MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE );

if ( !buffer )

throw std::bad_alloc( );

const auto instance = new ( buffer ) T( std::forward< Args >( args )... );

return paged_ptr< T >( instance );

}In the code snippet above, we allocate memory, ensuring that the region is reserved in the virtual address space and committed in physical memory. Below is the implementation for the constructor of the ws::paged_ptr instance. This constructor is responsible for managing the allocation and ensuring the memory starts outside of the working set.

The key part of this design is that we use VirtualUnlock during the construction phase to remove the memory page from the working set, making sure it's paged out. This ensures the page won’t be in physical memory immediately after allocation, allowing the operating system to manage it based on usage patterns. Additionally, the memory is added to the watch list, so future accesses can be tracked for changes.

paged_ptr( T* instance ) : instance( instance ), locked( false )

{

// We initially unlock the memory so that the page is not in the working set.

if ( instance )

VirtualUnlock( reinterpret_cast< LPVOID >( instance ), sizeof( T ) );

// Add the instance to the watch list.

watcher::get( )->add( reinterpret_cast< std::uintptr_t >( instance ) );

}Now we need a way to safely access this memory. This is where the implementation of the lock() function. This function moves the memory into the working set and provides a shared pointer to access the memory safely. The design ensures that the memory is locked into the working set only when it is actually needed.

/// <summary>

/// Moves the memory into the working set and returns a shared pointer to the memory. This is the only way to access the memory.

/// </summary>

std::shared_ptr< T > lock( ) const

{

// If the current memory is not locked in the working set, we lock it.

if ( !locked && instance )

{

VirtualLock( reinterpret_cast< LPVOID >( instance ), sizeof( T ) );

locked = true;

}

return std::shared_ptr< T >(

instance,

[]( T* ptr )

{

// Now we call virtual unlock twice:

// 1. To unlock the memory.

// 2. To remove the page from the working set.

VirtualUnlock( reinterpret_cast< LPVOID >( ptr ), sizeof( T ) );

VirtualUnlock( reinterpret_cast< LPVOID >( ptr ), sizeof( T ) );

} );

}We've created the ws::paged_ptr data type and can use it in our code. Assuming the working set watcher is running simultaneously on a separate thread, we can use the pointer like so:

// Allocate a 10-byte array of paged memory

const auto& paged = ws::make_paged< std::uint8_t >( 10 );

// Lock the page in memory so that we can safely access it's data

if ( const auto& data = paged.lock( ) )

{

// Get the raw pointer to the data.

const auto& ptr = data.get( );

// Edit the memory

ptr[ 0 ] = 0xFF;

ptr[ 1 ] = 0xFF;

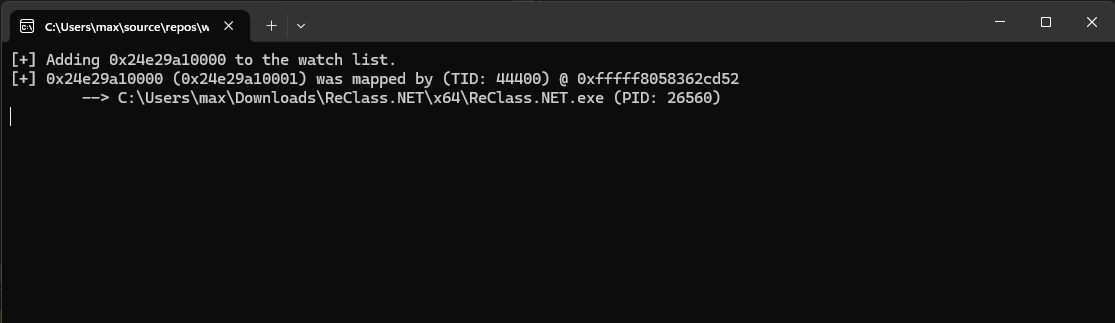

}Our watcher captures all unauthorized access to memory protected by the ws::paged_ptr data type and logs it to the console. Below, I've attached a screenshot of such a scenario, where ReClass (opens in a new tab) attempts to read from a remote address in our process.

Conclusion

In this post, we explored the concept of the working set in Windows processes and how it plays a crucial role in efficient memory management. By understanding how memory pages are loaded into and removed from the working set, we can manipulate the system's memory management mechanisms to monitor specific regions of memory for external access.

The working set watcher we implemented takes advantage of the GetWsChangesEx API to detect changes in the working set, allowing us to capture and log page faults triggered by external processes trying to access protected memory. This approach can be particularly useful in scenarios where securing memory from unauthorized access or external monitoring is critical, such as in anti-cheat systems, malware detection, or sensitive data protection.

Additionally, we introduced the ws::paged_ptr data type to manage memory more effectively, ensuring that specific pages remain outside the working set until explicitly needed. The integration of VirtualLock and VirtualUnlock APIs allowed us to control when and how these pages are moved in and out of the working set, giving us more fine-grained control over memory access.

By combining these techniques, we can not only optimize memory usage but also detect unauthorized attempts to read or modify memory in real-time. This approach opens up possibilities for improving system security and performance in applications where memory management is critical. The working set can thus be "abused" in a controlled manner to gain visibility into memory access patterns and detect potential threats.

With tools like the working set watcher in place, we can protect critical memory regions and respond to unauthorized access quickly and effectively. This method adds an extra layer of monitoring and security in Windows applications.

For more details and to explore the code, this project is available via my GitHub: ws-watcher (opens in a new tab).